As Community Medicine residents, our work often takes us beyond hospital walls—into the heart of communities where health, living conditions, and social realities intersect in complex ways. While our textbooks speak of community engagement in idealistic terms, the ground realities often offer a stark contrast.

Recently, as part of our residency, each of us was assigned to conduct a community survey in a densely populated urban slum in Mumbai. The task was to visit 20 households and complete at least five surveys each day. What seemed straightforward in planning turned out to be anything but simple in execution.

When Questions Feel Too Personal

The survey forms were comprehensive, designed to assess the socio-economic determinants of health. But in doing so, they delved deeply into people’s personal lives. We asked about monthly ration consumption, fuel usage, income, savings, housing quality, and more. While these questions serve a public health purpose, to the respondents, they often seemed intrusive.

“Why are you asking about our ration details? Are you going to give us something?”—this was a question I heard more than once. And I had no easy answer. The reality is, many residents are not receiving benefits they are eligible for. Some have no ration cards, others have stopped applying after facing repeated denials and unresolved complaints. There is an overwhelming sense of distrust and disillusionment. From their perspective, we were yet another group collecting data without offering any tangible help.

As a resident, this created a sense of helplessness. We identify problems, document them, and submit reports. But change is a slow-moving process. The system takes time—sometimes too long. And in many cases, the impact of our efforts won’t be visible within our tenure.

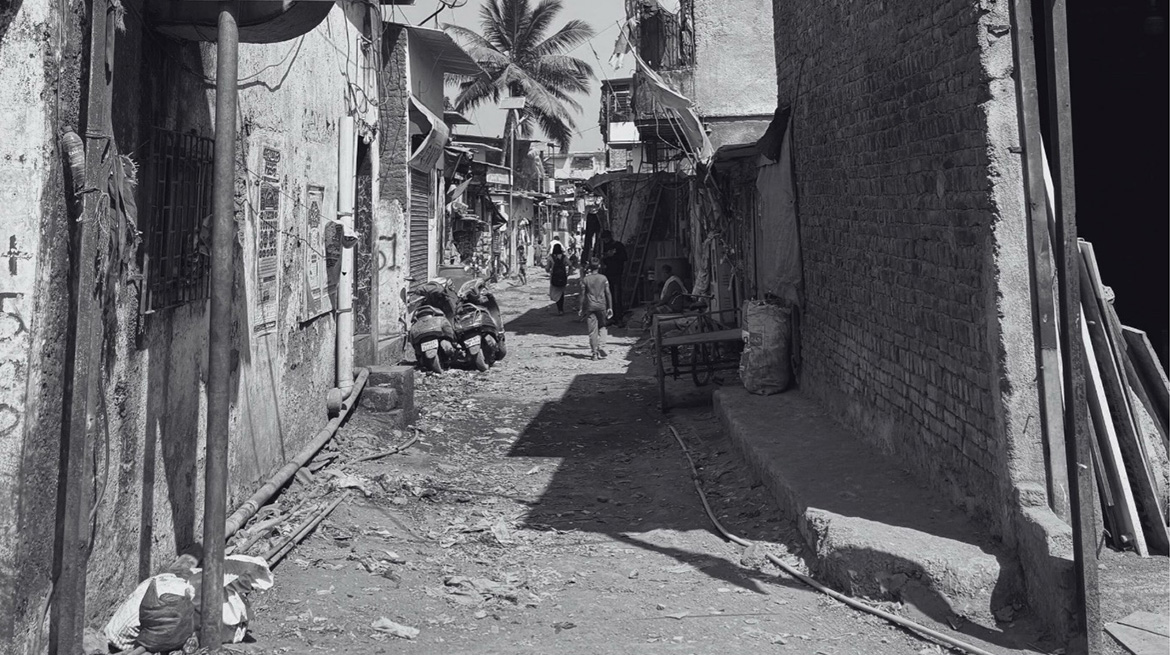

(Image 1: Picture taken while conducting the survey – marking our path through the community to remember the houses and find our way out.)

The Long Road—Literally

Commuting presented a challenge of its own. Most of us travel 1.5 to 2 hours daily (Approx 26 km) to reach our Urban Health Training Centre (UHTC). From there, we travel further to reach the survey site. Add to that the scorching sun, humid air, and narrow by-lanes filled with sewage water, and the physical toll becomes evident.

Sanitation in the area is poor, the stench of waste is constant, and drinking water is rarely offered by households. We rely on our own bottles, which often fall short. If buses are unavailable, we pay out-of-pocket for auto rickshaws. Meals, water, snacks—everything comes at personal expense.

Ironically, when we conduct health programs at the UHTC, refreshments and food are reimbursed through college funds. But when residents go into the field, often miles away from base, there is little to no financial support. This lack of institutional backing can be disheartening, especially when we’re expected to serve the underserved without being equipped ourselves.

(Image 2: “How does one live like this, I wondered—

Not for the first time, yet still with disbelief.

In 2025, such scenes should be memories,

Not realities etched into narrow lanes.

Something deep within whispers,

This isn’t how the world should be”)

Gender Sensitivity in Field Surveys

Certain sections of the survey focused on menstrual hygiene, contraception practices, and STI awareness. These are important, yet sensitive topics—particularly in conservative urban slum communities. Many female respondents were visibly uncomfortable discussing such matters with male doctors.

A simple yet effective solution would be pairing one male and one female doctor to conduct each survey. This arrangement would not only create a more comfortable environment for female respondents but also ensure that female residents feel secure when interacting with male-only households. Moreover, it would make counseling on menstrual health and reproductive issues more approachable and effective.

Moving Forward

Conducting community surveys is more than just a data collection exercise. It’s a window into the realities of the communities we aim to serve. It tests our clinical skills, our empathy, and our endurance.

But for community-based work to be sustainable and impactful, it needs systemic support. Residents require more than motivation—we need logistics, sensitivity training, and institutional backing. A stipend for fieldwork, better planning for gender-sensitive topics, and acknowledgment of the on-ground difficulties can go a long way in improving both the experience and the outcomes of such surveys.

We may not be able to change the system overnight. But by voicing these challenges, we take one step closer to a more empathetic and effective approach to community medicine.