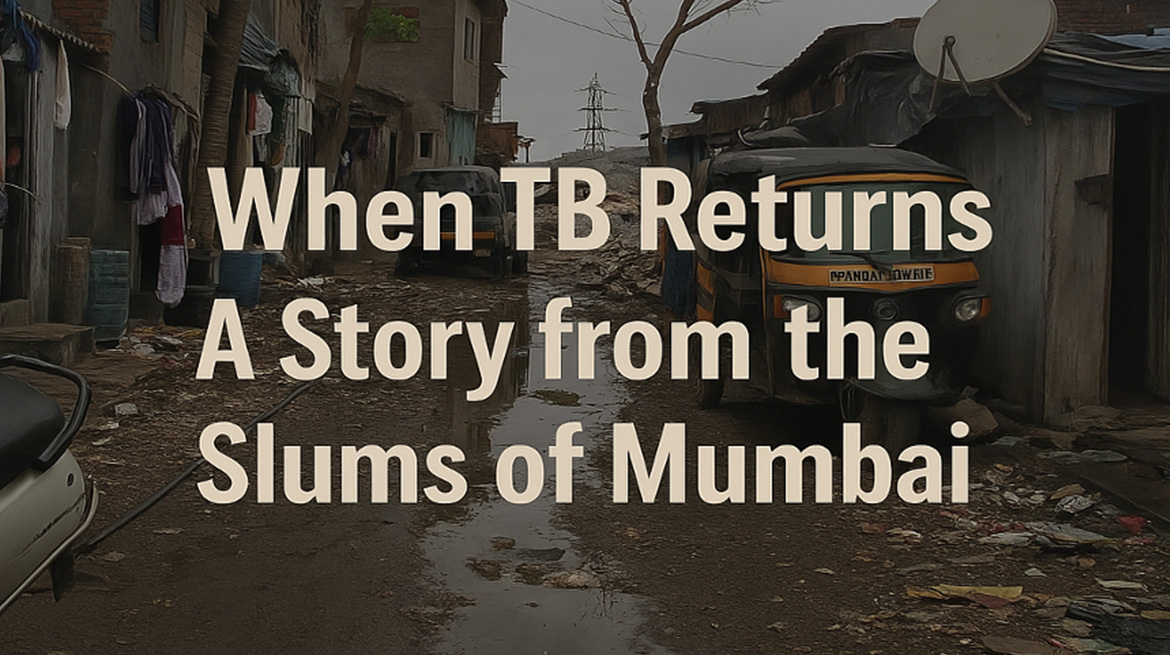

It was during my second year of post-graduation in Community Medicine when I was posted at the Urban Health and Training Centre (UHTC) in Malvani, Mumbai, an area characterized by dense population, poverty, and suboptimal living conditions that I encountered a case that profoundly influenced my understanding of tuberculosis (TB), not just as a medical condition, but as a reflection of broader social and environmental determinants.

It was just another day in the outpatient department at our Urban Health and Training Centre (UHTC) in Malvani, Mumbai when Mrs. Jayshree Laxman Nishad walked in. Thin, tired, and quietly hopeful, she came for a follow-up of her tuberculosis (TB) treatment. Her face was etched with hardship, and as a budding public health professional, I had learned to see beyond the symptoms to the story that brings the patient to us.

Jayshree, a 40-year-old widow, is not a stranger to TB. She’s lived through it, diagnosed first in 2007, then again in 2011, 2013, 2016, and now once more in 2021. A recurring pattern of infection, partial treatments, defaulting due to family emergencies, and sheer survival against odds. But her case wasn’t just medical. It was deeply social.

The Home Visit: Where Health and Habitat Collide

Driven by concern and curiosity I decided to visit Jayshree’s home in Ambujwadi, Malvani, accompanied by my PG batchmate. As we made our way through narrow, crowded lanes dotted with crumbling chawls and open drains, we reached her residence: a single 10×20 foot room, housing two people—Jayshree and her 20-year-old son, Santhosh.

The door creaked open to reveal a muddy floor, no windows, walls that weren’t cemented, and a low ceiling trapping heat. There was no cross-ventilation, and natural light barely seeped in. The air felt heavy, stagnant.

The kitchen was a makeshift corner with uncovered storage for food and no exhaust or chimney. Smoke from the LPG stove lingered in the same air they breathed. Drainage was open, attracting flies, and the home lacked a dustbin, so waste was thrown in a common dumping site 200 meters away.

Rodents scurried, mosquitoes buzzed, and Jayshree used coils to keep them at bay. There were no pets—but no peace either.

The toilet? Shared. One of the many public facilities built by the BMC and used by dozens. Water? Borrowed. Jayshree collected it in plastic containers from a neighbour who had access to a private water tanker. Drinking water was filtered through a sieve, not boiled.

Life Beneath the Surface: The Human Side of Disease

Jayshree’s story reflects the invisible reality of millions in urban slums. Her BMI was just 15.6, and her daily diet provided barely 940 Kcal and 23.5g protein, far from the nutritional requirements of a TB patient. She was illiterate, unemployed, and emotionally burdened, widowed in 2009, with her daughter lost to an illness and a son who suffered from seizures and worked hard just to put food on the table.

Despite it all, she remained compliant with her TB medication and attended every follow-up. She was aware of her illness, used masks appropriately, and practiced basic hygiene. Her resilience was remarkable.

But this resilience had limits.

Tuberculosis: A Symptom of Something Deeper

Jayshree’s case is a prime example of how TB is not just a bacterial disease, it is a social disease.

Infections like TB don’t just spread through sputum, they spread through poverty, poor housing, nutritional deprivation, limited access to clean water, poor ventilation, and compromised immunity. Her case had every social determinant of ill-health imaginable:

- Low income (₹3000/month)

- Inadequate nutrition

- Unsanitary surroundings

- Poor ventilation

- No access to safe drinking water

- No health insurance

- Shared sanitation

- Psychological stress due to COVID-related job loss

Even the best medical treatment struggles to work in such conditions.

What We Did and What More Needs to Be Done

We continued her treatment under the National TB Elimination Programme (NTEP)—providing free medication, a small cash benefit of ₹500/month for nutrition, and dry ration via an NGO. We also provided health education and encouraged her son to take preventive steps.

But what Jayshree needs goes far beyond ATT (anti-tubercular therapy). She needs housing with ventilation, a stable income, nutritious food, safe water, and emotional support. She needs dignity.

Reflections from the Field

After my experience that day, I’ve learned that diseases don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re woven into the fabric of life, where you live, what you eat, how you work, and how society supports you.

We can’t end TB unless we address what keeps it alive: inequality.

And so, as I stepped out of that single-room home in Malvani that day, I carried with me more than a case study, I carried a renewed urgency to advocate for policies that put health in the context of human living.

Because no one should have to choose between treatment and survival.