Act I: The Enduring Appeal of Prevention

“Prevention is better than cure” is an old adage with timeless resonance. History proves its worth: humanity’s greatest triumphs over disease—clean drinking water, safer roads and workplaces, hospital antiseptics, declining smoking rates, widespread immunization, and efforts to curb HIV—rely on stopping trouble before it starts. These victories showcase our ability to outsmart nature’s threats through foresight and action.

Yet, this same impulse underpins our quirks and follies. Superstitions, from knocking on wood to elaborate rituals, reflect a deep-seated urge to ward off misfortune. We’re desperate to believe human effort can shield us from fate’s cruelty, especially death—a fear so primal it devours rationality. The irony? While prevention aims to free us from illness, it’s also tethered us to a hyper-medicalized existence. We’re the healthiest generation ever, yet disease anxiety looms larger than ever, driven by an obsession with staying one step ahead.

Act II: The Double-Edged Sword of Early Detection

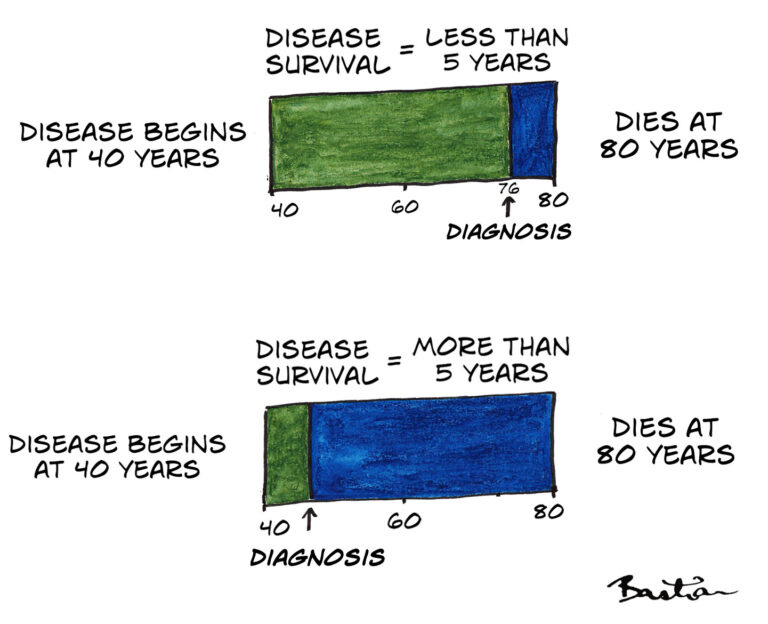

Ignoring symptoms, missing a stealthy infection, or shrugging off medical help can lead to catastrophe. Awareness and timely action save lives. But there’s a catch: catching something too early can be a hollow victory. It seems odd to call that a problem, but it is. Some conditions—like certain cancers or chronic diseases—unfold so gradually they might never threaten us. Diagnosing them early doesn’t extend life; it just prolongs the time we carry the label “sick,” eating into our disease-free years.

Ignoring symptoms, missing a stealthy infection, or shrugging off medical help can lead to catastrophe. Awareness and timely action save lives. But there’s a catch: catching something too early can be a hollow victory. It seems odd to call that a problem, but it is. Some conditions—like certain cancers or chronic diseases—unfold so gradually they might never threaten us. Diagnosing them early doesn’t extend life; it just prolongs the time we carry the label “sick,” eating into our disease-free years.

This trap, called “lead-time bias,” distorts survival statistics. A five-year survival rate looks impressive when diagnosis shifts earlier, but it’s an illusion—life expectancy stays the same. Even doctors stumble into this pitfall, misled by numbers that promise more than they deliver. It’s why early detection often falls short of the dramatic wins we expect. Beyond medicine, this pattern repeats: Dorothy Bishop highlights it in early reading interventions for kids, and Jon Brock sees it in theories about spotting autism in infants. Acting early without evidence can mislead us into false confidence.

Act III: Screening’s Hopeful Mirage

Screening feels like a no-brainer—who wouldn’t want to catch disease in its tracks? Yet, only some screening truly helps, and all of it carries risks. That flips the script on what many assume. Lead-time bias is one reason benefits get overstated; another is the “healthy volunteer effect.” People who opt for screening tend to be healthier or more proactive, skewing outcomes in their favour regardless of the test.

For screening to matter, it must beat symptom-driven diagnosis, rely on accurate and acceptable tests, and pair with treatments that work pre-symptoms. Too often, it doesn’t. People misjudge this: “Her cancer was found after symptoms, so I need screening,” they think, instead of “I should heed symptoms.” Others ignore warning signs, lulled by a clean screening result. When early intervention fails, some push for “pre-disease” checks—an optimistic leap that rarely pays off, landing us in what I’d call the “pre-disappointment phase.”

Act IV: The Screening Wars

There’s a science to evaluating screening—robust methods exist, and good intros are out there. You’d think we could settle which programs work. But emotion hijacks the conversation. Preventing disease stirs high stakes, and ideological trenches have formed: pro-screening zealots versus anti-screening sceptics. This divide isn’t just for laypeople; scientists fall in too.

Michael Marmot, who led a UK panel on mammography, saw this firsthand. He wrote that evidence gets filtered through biases—both in how it’s interpreted and how it’s produced. Assumptions often trump data. Glance at an article’s author, he noted, and you can guess their stance. This tribalism clouds what should be a rational debate, leaving us wrestling with feelings rather than facts.

Act V: The Heavy Toll of Over-Diagnosis

The illusion of prevention comes at a cost. Those who’d benefit most—say, from better access to proven measures—often lose out. Resources shift to the over-diagnosed, a twist Margaret McCartney dubs “the patient paradox” and Julian Tudor-Hart called “the inverse care law.” Fearful health campaigns can even backfire, amplifying dread instead of easing it.

Then there’s the growing army of the over-diagnosed—people battling “diseases” that’d never have struck, enduring toxic treatments or surgeries for naught. As diagnoses climb, so does the ripple effect: we’re more likely to know someone touched by this, spreading a cloud of unease. The “what if” haunts us—did early detection save us, or was it a mirage? Personal stories of dodging fate cement the myth, making perspective elusive. We need more voices who grasp clinical research’s nuances and share them clearly, sidestepping bias.

We’ve learned to ditch “cure” for “treatment” to curb inflated hopes. “Prevention” needs the same scrutiny—less a magic shield, more a tool with limits we must respect.