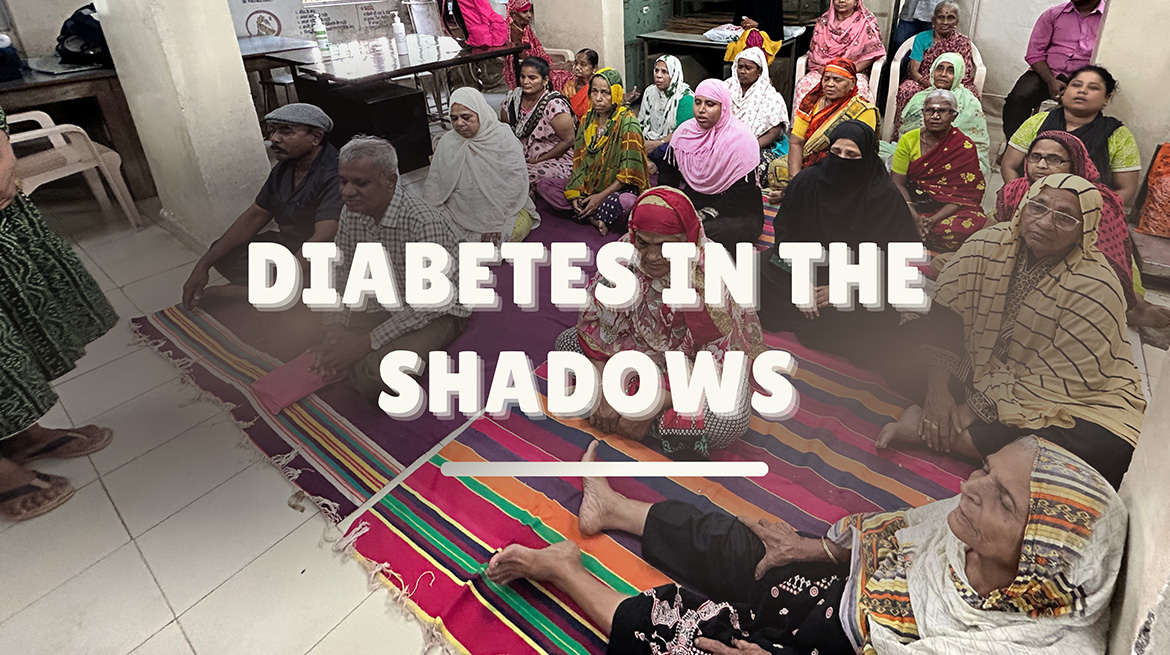

In my Community Medicine residency, I’ve come across many health challenges, but few have left a deeper impact than seeing how diabetes takes its toll on the elderly in urban slums. The people I meet have lived a lifetime of resilience yet are shadowed by the relentless demands of managing diabetes in poverty. These are grandmothers and grandfathers, often without family support, who rely entirely on the public health system to get by. They shuffle through daily life with no guarantees that the medication they need will be there tomorrow. They skip meals when they have to, make do with half doses of insulin or wait for hours at clinics that struggle to meet their growing needs. Many live with uncontrolled hyperglycaemia that no amount of available medication can stabilise; others silently endure pain and complications made worse by hypertension, obesity, and smoking.

The Socioeconomic Burden of Diabetes:

Diabetes in an urban slum isn’t just a disease; it’s a sentence to a lifetime of dependency on an underfunded public health system. Elderly patients often spend hours in overcrowded clinics waiting for medication, only to find that supplies are depleted. Sometimes, the public health system provides only the basics, which are inadequate for those with uncontrolled hyperglycaemia who need more complex regimens. Patients can be referred to higher centres for changes in treatment plans. Often, they cannot afford to make these journeys due to transport costs or because they have no one to accompany them. For some, it is the choice between buying a bus ticket or buying food. For them, accessing the necessary medications is about navigating a maze of referrals and bureaucracy, a difficult task when every rupee counts and health conditions make even a short journey challenging.

In these communities, diabetes rarely comes alone. It’s complicated by obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol, and a range of other chronic conditions. Patients are often caught in cycles of polypharmacy, dependent on multiple drugs that they may not need, and that the system cannot consistently provide. I’ve seen eyes filled with quiet resignation as they tell me about the medications they juggle—pills for heart disease, high blood pressure, chronic pain, indigestion and sometimes, for a persistent cough that’s gone untested for TB. The lack of reliable access to insulin is a particularly dangerous gap, leaving many to manage with insufficient doses or erratic supplies. A skipped dose is not just an inconvenience; it’s a risk of hospitalisation, even death. When patients are repeatedly advised to change diets or medication regimens that are unsustainable on their income, they simply revert to what they know, leading to even more health complications over time.

The cultural and financial realities in these areas make dietary recommendations challenging. In our field practice area, red meat and fried food are affordable and easily available, making them a staple despite their impact on cholesterol and heart health. And while families sometimes step in to help financially, these elderly patients often hesitate to burden their children, who are struggling to make ends meet themselves. This dependency takes an emotional toll; for many, the shame and guilt of relying on others only add to their isolation and anxiety.

TB, a persistent health threat in urban slums, complicates the picture further. Diabetes increases the risk of developing active TB, yet the stigma around TB and the reluctance to get screened are widespread. Missed cases are common, and patients often unknowingly delay treatment, adding to their suffering and the spread of the disease. The situation is even more dire for women with gestational diabetes. Without referral care, these high-risk pregnancies go unsupported, putting both mothers and infants at risk. They, too, face the economic barriers of travel and are left without sustainable treatment options, another reminder of how inequities in healthcare can cut across generations.

Every visit to these slums teaches me something new, often in ways that no textbook could capture. Here, diabetes isn’t a condition to be managed with a set of prescriptions; it’s a daily struggle that demands courage, resourcefulness, and resilience. It is a reminder that healthcare is not a privilege, it’s a right. As I listen to the stories of those who have no one to rely on but the public system, I feel both their quiet strength and their quiet despair.

On this Diabetes Day, we cannot settle for awareness alone. We must commit to systemic changes to bridge these gaps and create a health system that doesn’t just survive but sustains those who need it the most. This could mean pushing for better and more consistent medication supplies, setting up accessible clinics with the help of NGOs within slum communities, ensuring routine screenings and support for high-risk patients, including those with TB and pregnant women, upskilling healthcare providers posted in slums and improved insurance coverage for accessing diabetic control services, even on an outpatient basis. Each step we take can lighten the load for someone, allowing them to live with dignity rather than dependence.

When I talk about tackling diabetes, I will always remember these faces and stories. Together, let us hope to work towards a future where we fight not only against diabetes but for the dignity, health, and hope of every life touched by it.

Really great and very nicely put forth👍 Proud to state that Dr.Shwetangi is my PG student and is really dedicated to community medicine.Keep it up Shwetangi👍proud of you👍